The following article is the follow-up synopsis of everything I learned about the design behind P&C adventure games while playing and analyzing the game Broken Sword II - The Smoking Mirror. (To see the web series where I played and analyzed the game, please click

here)

A theme that kept jumping out to me while I played Broken Sword II - The Smoking Mirror was how items and dialog were used to communicate it's story-line. I noticed that the progression of the story was often at the whim of the proper usage of a certain item or a dialog with a NPC (non-playable character). Since the success of a P&C adventure game relies mostly on a well delivered story, it seemed well meritorious to further explore their relationships with these two elements.

After what accrued to be an unnecessary amount of analysis I came to a conclusion that would have eluded the foresight of even the most powerful of wizards. I concluded that there are two types of point and click adventure games: P&C games with inductive game play and P&C games with deductive game play. I know, inductive and deductive are words never before with P&C games, but there is reason for this trespass. I came to use these terms partly because they are very prevalent in my studies (I'm taking some courses on research), partly because I am trying to marry my skills as a designer of educational material with my skills as a designer of entertainment material, but mostly because they fit each other in the most eerie of ways. I will first give context to these words outside of games, and then show how I connected them to P&C games.

Inductive and deductive are words most typically used with how humans use reason to acquire knowledge. To reason

inductively is to take a number of experiences with a topic, find a common theme among them, and draw a generalization about the topic from this theme. For example - I have dated 5 women between the ages of 20 and 30. Once a month all five of these women would have a menstrual related experience. I inductively reason from these experiences that all women between these ages share similar menstrual experiences.

Deductive reasoning, on the other hand, is the complete opposite. To continue with the previous example - With little to no personal experience I deduce that the woman I am dating will have a menstrual related experience at least once a month simply by that fact it is widely considered true that she will. Inductive reasoning relies on the individual drawing heavily from personal experiences to define the parameters of a situation while deductive reasoning relies on the individual drawing heavily from outside experiences to define the parameters of a situation.

Now how does this translate into P&C games? To help the reader understand that I will take elements that all P&C adventure games share and show how they differ under the inductive/deductive microscope. I will use the keywords

personal and

outside experience from above throughout this article to help with this differentiation. Hopefully you will notice patterns of how the shared elements of the game change as they go from one side of the spectrum to the other.

Puzzles

Puzzles are a very defining characteristic of P&C games. Some puzzles are just refurbished versions of classics like this puzzle from A Whispered World:

But what if you need to find a detonator so you can blow your friend out of jail? Or find some ingredients for a potion that will cure your hand of a disease that causes it to randomly punch you in the face at the most inopportune moments? These puzzles resemble more of a laundry list then anything else. But within the confines of a P&C adventure game they are all considered puzzles. In P&C games a puzzle is defined as anything that stands in the way between you and the progression of the story. Their varied shapes, however, do start to make more sense under the lens of our inductive/deductive microscope. Remember that inductive reasoning uses personal experience to draw meaning and therefore is used when the parameters of a situation are unknown and all the player can use IS his personal experience to solve a puzzle. If you are playing a P&C adventure game and you often find yourself running around trying to find items, or using random items with other random items with the hope they fit together, or just often ask yourself, "What the hell am I supposed to do?", it means you are playing trying to solve a puzzle within a situation that has

not been clearly communicated to you. You need to use the various

experiences you have of interacting with items, the environment, and NPCs, within that situation to induce what the solution to the puzzle would be. You are playing an inductive P&C adventure game. An example of this would be if the game communicated to you via an NPC that you need to fix the windmill so that you can provide power to the cottage and survive the cold winter. After this point you receive no other pointers from the game. It is up to you, the various experiences you have with your environment, the items you have in your backpack, and your ingenious ability to make the right connections (or use a walk through) to solve the puzzle. You can adjust the difficulty settings of the game to allow for explicit hints to be given but that is not considered part of the story design so it is irrelevant to this article. (I am however experimenting with how to have a difficulty setting be an integral part of the story design.....still need to write an article on that though) A deductive game design approach would mean you rely solely on what is communicated to you by the game to solve the puzzle -

outside experience dictating what you do. Now if this approach was used to design the windmill puzzle I just used that would be a very boring puzzle. The game would not only tell you that you need to turn the windmill on, but tell you each step in the process. There would effectively be NO puzzle!

So what does a puzzle in a deductive P&C game look like? Well you just need to think of a puzzle that has clearly defined parameters or, in this case,

rules. If you refer back to the picture above you will notice some writing on the top left. That is the

outside experience a person used to design the puzzle being communicated in the form of

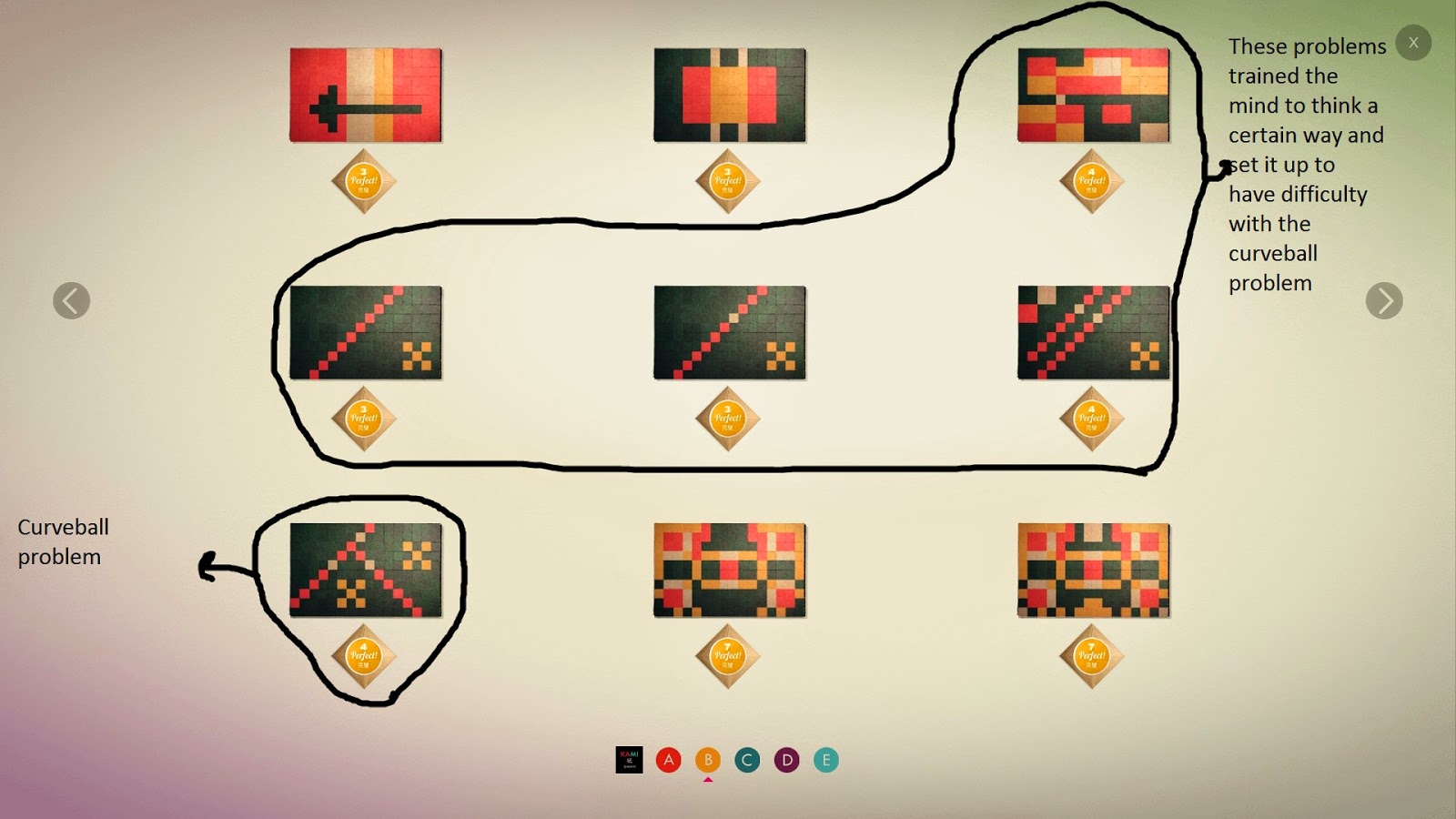

rules of how to solve the puzzle. The player who wants to solve that kind of puzzle CAN'T use personal experience to solve it because he has none. If he did, he would already know the solution! Puzzles in deductive P&C games therefore tend to take the shape of mini games with well defined rules that have been purposely designed to be exceptionally hard to solve within those set rules. Puzzles like these didn't exist in traditional P&C adventure games like Monkey Island, but games like Puzzle Agent have changed this. Why you may ask? Well, puzzles in inductive P&C games don't lend themselves well to numbers and stats. I mean how do you place a numerical value on turning on a windmill? You either do it and live, or don't and die. On one hand deductive P&C games gained popularity because screens like this:

are crack to some gamers.

Now some of you may be telling yourself, "Well, I don't care if I get 10 stars for solving a puzzle on my first try. There is no emotional weight there. I would feel much more motivated to solve a puzzle of turning on a windmill because I know otherwise I could die!". And this very thought beings me to the next element shared by both inductive and deductive P&C games.....

Story

The desire for a well designed and delivered story is the reason P&C adventure games came into existence. The whacky characters of Space Quest, the dark comedy of the Grim Fandango, are all memorable because of our innate attraction to a good story. This was the birth the birth of the P&C adventure game genre though it is not is sole state today. Since the days of Monkey Island, P&C adventure games have undergone various makeovers. For the purpose of this article I will stay within the confines of inductive and deductive games (although if you have played Gemini Rue, you will have seen elements of action start to creep into the genre and I have no clue how that fits into my inductive/deductive model)

Since inductive P&C games rely much more heavily on how the player interprets his own personal experiences with other characters, the environment, etc, it requires the player to get more emotionally involved with the story - of course, the answers to the puzzles are communicated VIA the story! This thus puts great responsibility on the designer to assure the most engaging story is produced and delivered in the most engaging way. Failure to do so would undoubtedly result in a bored gamer. Deductive P&C games, with their emphasis on incredibly challenging mini games the solution of which is generally detached from the story line altogether, are more geared towards gamers who like well-defined rules wherein they must obey in order to prosper. These gamers would also enjoy games from the puzzle genre as well. This means there is not as much of an emphasis on developing an interesting story because the gamer is, after all, just waiting for the next opportunity to score a perfect 0, get those 10 stars, all the while having insane stimulation to his cognitive brain muscle. Thus, games on the inductive extreme would have very complex and elaborate story lines where the player is pitted against himself in inducing the solution to all the pitfalls that await him while on the deductive extreme the player is less concerned with how the story unfolds and more concerned with how mentally challenging the puzzles are.

There are, of course, few games that fall on any of these extremes. Most P&C games these days fall somewhere in between. This is OK - sometimes. Sometimes what happens is you get a game that doesn't know what it is. It tries to be inductive when it should be deductive and vice versa. This is the reason I went to such depths to try to define these two types of games from the same genre. As a person who wants to one day design my own P&C adventure (and as a teacher who thinks these games are the missing link to make edugames actually fun games) I felt I needed to properly define the various types of P&C games I have played so I could understand what they did right and where they could have improve. For example, at the very end of Broken Sword II - The Smoking Mirror there was a

puzzle designed typically for a deductive P&C game - but Broken Sword II - The Smoking Mirror was clearly an inductive P&C game. This isn't to say it was wrong to include a deductive-type P&C puzzle in an inductive game, if the puzzle was properly designed. What I had to endure was a puzzle that took 15 seconds to solve, but 5 minutes to complete. It was long, boring, and horribly designed. I think this could have been avoided if the designers clearly knew the difference between inductive and deductive P&C games and designed accordingly. That is what I plan on doing.

There are still many more aspects of P&C games I need to understand. My deductive/inductive model may eventually lack the integrity to hold up under the pressure of all the other elements I am still to discover. Who knows. I am not THAT I love with it. I will continue to play these games, continue to analyze them, and most importantly continue to design my own.